‘Mückenatlas’: A citizen science project for mosquito surveillance in Germany

The EU faces a rising threat of mosquito-borne diseases, with climate change contributing to the spread of disease-carrying mosquitoes. In Germany, the 'Mückenatlas' citizen science project engages the public in collecting mosquito samples, serving as an early warning system for disease outbreaks.

Disease agents transmitted to animals and humans by mosquito bites have gained attention throughout the EU, as cases of dengue, chikungunya and West Nile Virus (WNV) have been recorded, especially in southern Europe. However, the spread of the mosquito species carrying these disease pathogens (such as viruses, bacteria and parasites that can cause diseases) has also been documented in more northern countries, including Germany. Climate change has been recognised as one of the factors contributing to this spread. To address the potential health risks, surveillance, prevention and abatement measures need to be combined. The German ‘Mückenatlas’ (‘mosquito atlas’) is an example of how a citizen science project can not only contribute to research, but also supplement traditional monitoring methods to function as an early warning system. The project engages citizens who submit mosquito samples, which are then identified and used for research by experts. The ‘Mückenatlas’ therefore contributes to knowledge on native and invasive mosquito species and related diseases in Germany, and seeks to establish an information base for policy makers and researchers to assess future risks.

Case Study Description

Challenges

Mosquitoes are one of the vectors that can potentially transmit vector-borne disease agents, i.e. pathogens that are transmitted between animals (vertebrates) and humans by the bite of infected arthropods. Mosquito-borne diseases have gained attention throughout Europe as cases and outbreaks of dengue, chikungunya and West Nile have increasingly often been recorded in southern Europe since the late 2000s (Engler et al., 2013; Schaffner et al., 2013).

In addition to intensified international trade, whereby invasive species are imported by long-distance transport, the effects of climate change, such as rising temperatures and increased precipitation in some areas, have been identified as factors contributing to the occurrence of the mosquito vector species (European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control [ECDC]; Vector-borne diseases ). Climate change can prolong the transmission periods in places where vector-borne diseases are already present and can improve climatic suitability for invasive mosquito species in areas that were previously less suitable.

Aedes albopictus (Asian tiger mosquito), one of the most prevalent invasive species, acts as a vector for dengue, chikungunya and zika virus (Paz, 2021). For this species, improved climatic suitability is projected for central Europe and the Balkan region, while drier conditions in areas such as Spain and Portugal could reduce the climatic suitability in long term (Semenza and Suk, 2018).

The effects of climate change on the population of Aedes japonicus (Asian bush mosquito), another prominent invasive species that could especially spread WNV and Zika virus, is less clear. Nonetheless, some scientists suggest a continued high suitability of areas in Germany in the future (Kerkow et al., 2019). Southern Germany in particular is projected to become highly suitable for this mosquito species and might be one of the few regions where both Ae. albopictus and Ae. japonicus could co-exist (Cunze et al. 2016).

According to recent figures by the ECDC and EFSA (2021), Germany is currently the most northern country in Europe with several established populations of Aedes mosquitoes, which include Aedes albopictus and Aedes japonicus. First cases of WNV, which could primarily be spread by some of Germany’s native mosquito species, were recorded among birds and horses in 2018, and several human cases were reported in 2019 and 2020, mostly in Germany’s Eastern parts (Ziegler et al., 2019; 2020; Pietsch et al., 2020).

Objectives

Against this background, the monitoring of the presence of invasive species that could further spread disease agents is consiedered important, especially in areas at risk of importation, further expansion of existing populations, and pathogen transmission (ECDC, 2012). However, as native mosquitoes can also play a role in transmission, they need to be monitored as well (ECDC, 2014). Throughout Europe, surveillance measures have been set up to help the (early) detection of mosquito populations, their elimination and prevention of future establishment (National Expert Commission “Mosquitoes as Vectors of Disease Agents”, 2016). However, efforts are not integrated, and expertise and experience on vector surveillance and control should be enhanced to prepare for future challenges (ECDC, 2021; EFSA and ECDC, 2021b).

The emergence and resurgence of mosquito-borne diseases in southern Europe in early 2000s led to public financial support for research projects on this topic in Germany. This included the establishment of a mosquito monitoring program in 2011, which pursues a two-fold approach for collecting samples, using both traps and citizen participation within the so-called ‘Mückenatlas’ project. Since 2012, the ‘Mückenatlas’ project aims to improve the knowledge on where (and when during the year) native and invasive mosquito species occur and on their respective potential as vectors of disease agents, to ultimately support future health risk assessments in Germany.

Adaptation Options Implemented In This Case

Solutions

The ‘Mückenatlas’ is an example of a citizen science project, which aims to support systematic field work conducted by experts, by collecting mosquito samples throughout Germany. Citizens are asked to capture mosquitoes (undamaged) in their private surroundings, freeze them, fill in an accompanying form and subsequently post them to one of the two research institutions involved. The project’s website provides interested people with guidance regarding the capturing and contribution of mosquito samples, and how they are processed. Upon reception, experts identify the submitted mosquito species morphologically (by microscope) or genetically. Contributors then receive detailed information about their submissions. If children participate and this is indicated in the form, a special certificate is issued for them.

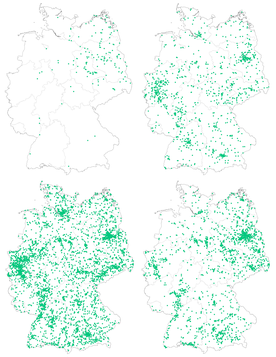

Whereas most contributions to the ‘Mückenatlas’ refer to native mosquitoes, the citizen science project has also contributed to recording invasive species of mosquitoes. In 2013, a considerable population of Ae. japonicus was discovered in the northern German town of Hanover, thanks to an earlier contribution to the ‘Mückenatlas’, as the area would likely not have been considered as a region for the spread of this species . It has been suggested that contributions to the ‘Mückenatlas’ have mirrored the spread of Germany’s currently-known Ae. japonicus populations, indicating that such a citizen science project can successfully help uncover changes in mosquito occurrences and assist the planning of targeted field surveillance measures . The first contributions of Ae. albopictus to the atlas in 2014 also led to the discovery of a locally breeding population in southern Germany. Almost all known populations of Aedes albopictus have been discovered after notifications by citizens, including through contributions to the atlas.

Local municipalities where these mosquitoes occurred were then notified in order to induce control measures, showing that Mückenatlas can function as a valuable early warning system. In at least two cases, early warning has led to the elimination of populations. Data on both native and invasive species, the location and date of capture are subsequently recorded in the German national mosquito database CULBASE and are used to map the distribution of mosquito populations throughout the country. In the future, the database will provide information to researchers and policy makers to facilitate modelling, risk assessments and management of mosquito-borne diseases.

Findings on Ae. albopictus are additionally reported to state offices for infectious disease epidemiology who forward the reported data to the respective health departments, the ECDC, as well as to the German National Expert Commission “Mosquitoes as Vectors of Disease Agents”.The ‘Mückenatlas’ has been linked and contributed to two larger research projects. Between 2015 and 2018, a monitoring project (‘CuliMo’ – “Culiciden / Steckmücken Monitoring in Deutschland”) driven by six research institutions throughout Germany recorded the geographical and seasonal occurrence of mosquitoes as well as potential pathogens. Part of the data was directly supplied by the citizen science project. The other research initiative (‘CuliFo’ – “Culiciden Forschungsprojekt”) specifically examined which invasive and native species are suitable to transmit mosquito-borne diseases in Germany between 2015 and 2019.

The ‘Mückenatlas’ itself relied on public outreach and media campaigns to raise awareness about the project and increase participation. Specific actions encompassed press releases, newspaper articles, interviews for radio and TV, presentations to the public and brochures.

Relevance

Case mainly developed and implemented because of other policy objectives, but with significant consideration of Climate Change Adaptation aspects

Additional Details

Stakeholder Participation

The ‘Mückenatlas’ is a collaboration between Germany’s Federal Research Institute for Animal Health (Friedrich-Loeffler-Institute [FLI]) and the Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) e.V.. They are responsible for identifying the mosquito species after citizens’ submission, conducting field research, storing and disseminating the collected data. FLI further hosts the National Expert Commission “Mosquitoes as Vectors of Disease Agents”, which has provided advice, guidance and recommendations on the topic of mosquito-borne diseases since 2019, especially focusing on the Asian tiger mosquito (Ae. albopictus).

As a citizen science initiative, people living throughout Germany who participate in the project are a crucial component of the project’s success. Since its inception in 2012, more than 30 000 participants have contributed more than 150 000 mosquito specimens. Media have contributed to raising awareness about the project.

A number of other research institutions, such as the Bernhard-Nocht-Institute for Tropical Medicine, were involved in the joint projects ‘CuliMo’ and ‘CuliFo’. Various researchers have used the ‘Mückenatlas’ both as a source of data and as a case study of citizen science in mosquito surveillance in scientific publications (e.g. Kerkow et al., 2019; Pernat et al., 2021).

Success and Limiting Factors

The large number of contributions indicates a level of success for the project, which has become an “excellent tool for large-scale passive mosquito monitoring” (Werner et al., 2014) and “efficient tool for data collection” (Walther and Kampen, 2017). The dialogue between citizens and scientists as equals, transparency, commitment and relevance have been stated as crucial success factors for the ‘Mückenatlas’, as well as for communication for citizen science projects more generally. In addition to varying mosquito occurrences due to season and geography, media coverage has influenced the number of submissions received .

The combination of citizens as data collectors, contributing samples without previous bias of selection, and scientists who do quality assurance by identifying the mosquitoes, leads to high quality of data (Kampen et al., 2015). While the number of mosquitoes collected in conventional traps are larger, the geographical distribution of citizen submissions is broader and the likelihood of random catches higher, compared to conventional traps. In addition, 66% of mosquitoes are caught in peoples’ homes, therefore providing the scientists with samples not available through the regular monitoring efforts (Pernat et al., 2021a). Therefore, this citizen-science approach contributes to expanding the knowledge on mosquitoes in urban areas and in human housing.

As the ‘Mückenatlas’ website points out, the citizens themselves learn about local biodiversity, and the ecology and biology of mosquitoes in their surroundings. According to the National Expert Commission “Mosquitoes as Vectors of Disease Agents” (2016), citizen participation and awareness are key to combatting mosquitoes, especially in residential areas. Whilst science has benefitted from improved data, the ‘Mückenatlas’ has served such educational purposes , considering the project’s accompanying media campaigns and feedback to contributors.

Nevertheless, there are aspects that could be seen as limiting factors. Due to the samples being submitted by non-experts, even 25% of contributions are insects other than mosquitoes (Walther and Kampen, 2017). Furthermore, the submitted data could be biased, e.g. with regards to spatial distribution or individuals’ preferences to capture invasive, ‘exceptional’ species (Pernat et al., 2021a). Further, as all citizen science projects, the ‘Mückenatlas’ depends on people’s awareness of its existence and willingness of individuals to participate and follow the procedures for capturing the mosquitoes correctly. The lack of financial reimbursement of shipping costs (even if a minor expense for some) as well as printing and filling out the required form might limit who is able to participate in the project.

Costs and Benefits

The Federal Ministry of Food and Agriculture (BMEL) funded the ‘Mückenatlas’ initiative. The two accompanying research projects (‘CuliMo’ and ‘CuliFo’) each received 2,2 million € funding from the Federal Ministry for Food and Agriculture to fund various monitoring and research activities, including activities related to the Mückenatlas. Within the monitoring project (‘CuliMo’) 2015 - 2018, which more specifically mentioned the ‘atlas’ as a subproject, FLI and ZALF received 735.768,00 € and 854.735,00 € funding respectively. Costs for mailing the mosquitoes to the research institutions are covered by the participating individuals, i.e. they are not refunded by the project. Participants are generally not remunerated financially, but receive information on their submissions after analysis and can be recorded as contributors on the ‘Mückenatlas’ website, if desired.

Surveillance measures that monitor mosquitoes and pathogens (infectious agents, e.g. a virus that causes a disease) have been identified as cost-effective ways of dealing with the health risks associated with mosquito-borne diseases (Engler et al., 2013) – “both human and financial costs of a potential epidemic can be contained” (Semenza and Suk, 2018). Thus, the citizen science-based approach of the ‘Mückenatlas’ could present further cost-saving potential compared to other surveillance methods. Its passive monitoring approach with citizen participation leads to cost-, time- and labour-reductions when compared to active collection, e.g. by setting up traps (Kampen et al., 2015).

Benefits of the initiative include, besides the contribution to the scientific research, increased citizens awareness on the mosquitoes spread, biology, and related risks.

Legal Aspects

The German government includes human health as one priority area in its climate change adaptation strategy (2008) and has specifically acknowledged the need to take action with regards to vector-borne diseases in its action plan (2011). Monitoring of native and invasive mosquito species and their potential to transmit disease agents is included in the specified measures. As part of their adaptation efforts in the health sector, the German Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation, Nuclear Safety and Consumer Protection informed the public about health risks associated with climate change in a 2020 publication. It explicitly mentions the ‘Mückenatlas’ as an opportunity for citizens to support monitoring mosquitoes that can contribute to the spread of diseases.

Implementation Time

The ‘Mückenatlas’ started in 2012 and citizens have contributed to its content ever since. Contributions can be sent-in all-year-round, but vary according to season, with more samples sent in the summer.

Life Time

Mosquitoes and vector-borne diseases data are continuously collected. The ‘Mückenatlas’ and the CULBASE database serve as information repository, supporting adaptation measures for health in the long term. The current funding period for the project concludes at the end of 2022. However, plans exist to prolong and institutionalize the project at ZALF, which follows the example of FLI, where the project has been integrated into systematic trap monitoring since 2019.

Reference Information

Contact

Doreen Werner

Leibniz Centre for Agricultural Landscape Research (ZALF) e.V.

Müncheberg (Germany)

E-Mail: mueckenatlas@fli.de

Helge Kampen

Federal Research Institute for Animal Health:

Institut für Infektionsmedizin

Greifswald – Insel Riems (Germany)

E-Mail: mueckenatlas@fli.de

Websites

Reference

Kampen, H., Medlock, J.M., Vaux, A., Koenraadt, C., van Vliet, A., Bartumeus, F., Oltra, A., Sousa, C.A., Chouin, S., Werner, D., 2015. Approaches to passive mosquito surveillance in the EU. Parasites & Vectors 8, 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-014-0604-5

Kampen, H., Tews, B.A., Werner, D., 2021. First evidence of West Nile Virus overwintering in mosquitoes in Germany. Viruses 13, 2463. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13122463

Kerkow, A., Wieland, R., Koban, M.B., Hölker, F., Jeschke, J.M., Werner, D., Kampen, H., 2019. What makes the Asian bush mosquito Aedes japonicus japonicus feel comfortable in Germany? A fuzzy modelling approach. Parasites & Vectors 12, 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13071-019-3368-0

Pernat, N., Kampen, H., Jeschke, J.M., Werner, D., 2021a. Buzzing homes: using citizen science data to explore the effects of urbanization on indoor mosquito communities. Insects 12, 374. https://doi.org/10.3390/insects12050374

Pernat, N., Kampen, H., Ruland, F., Jeschke, J. M., Werner, D., 2021b. Drivers of spatio-temporal variation in mosquito submissions to the citizen science project ‘Mückenatlas’. Scientific Reports 11, 1356. https://doi-org/10.1038/s41598-020-80365-3

Walther, D., Kampen, H., 2017. The citizen science project ‘Mueckenatlas’ helps monitor the distribution and spread of invasive mosquito species in Germany. Journal of Medical Entomology 54, 1790–1794. https://doi.org/10.1093/jme/tjx166

Werner, D., Hecker, S., Luckas, M., Kampen, H., 2014. The citizen science project “Mueckenatlas” supports mosquito (Diptera, Culicidae) monitoring in Germany, in: Proceedings of the Eight International Conference on Urban Pests. Müller, G., Pospischil, R., Robinson, W. H. (eds.), Hungary, pp. 119–124. icup1098.pdf

Published in Climate-ADAPT Jan 27 2022 - Last Modified in Climate-ADAPT Apr 18 2024

Please contact us for any other enquiry on this Case Study or to share a new Case Study (email climate.adapt@eea.europa.eu)