All official European Union website addresses are in the europa.eu domain.

See all EU institutions and bodies

© Växjö municipality

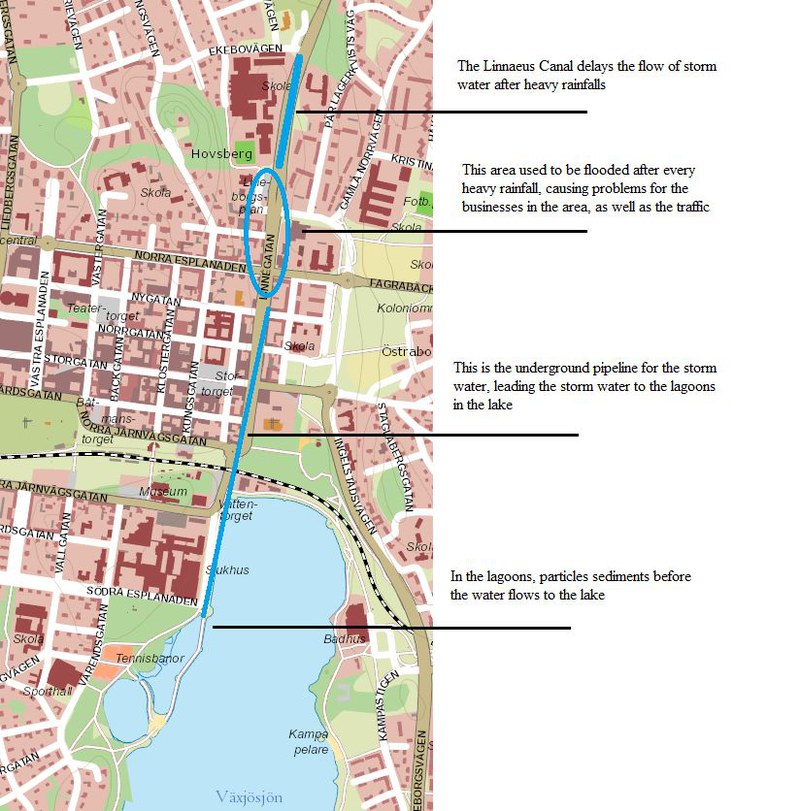

The Linnaeus canal and connected lagoons were constructed to prevent the frequent flooding of the nearby streets. While its dimensions had to be restrained due to urban space limitations, the canal provides benefits both in terms of environmental and water management targets.

The City of Växjö is situated in the southern part of Sweden, surrounded by forests and lakes. As many parts of the central city of Växjö were built upon wet and swampy areas they are vulnerable to floods after heavy rainfall events. One of the most affected parts is the street Linnégatan which is built on a previously existing small stream and which is situated much lower than the surrounding built areas. In past years, rainwater often flooded the street and the nearby buildings’ basements and cellars.

At the end of the 1990’s, the City of Växjö restored the canal in Linnégatan, i.e. the Linnaeus canal, in order to prevent the streets and surrounding areas from flooding and to regulate the flow of the storm water to the Växjö lake. The canal and connected sedimentation lagoons are an example of how adaptation to extreme weather events and other environmental targets, i.e. the water quality of the Växjö lake, can be combined in one system of integrated measures.

Case Study Description

Challenges

In the past, annual floods occurred and strongly affected the local infrastructure close to Linnégatan. Streets were flooded for several days and the cellars of nearby buildings were filled with water causing high cleaning and reconstruction costs. In the early 2000’s, there was little discussion about local climate change and its impacts; the guideline was to develop effective measures to prepare for 10-year rainfalls – not in the context of climate change but in the context of highly recurrent heavy rainfall events. Preparing for 10-year rainfalls means that instead of expecting floods after every heavy rainfall event, floods are expected only once every 10 years (corresponding to an yearly probability of occurrence of the given flood of 10%). As a result of the restoration of the Linnaeus canal, the city of Växjö has avoided many floods and is expected to avoid future flood damages as well.

However, since the construction of the canal, climate change projections have changed and now indicate more frequent and roughly 10% more intense extreme precipitation events for the future (SMHI).

The existing built environment often limits the dimensioning of new storm water management facilities in the city. In Växjö, climate change impacts are considered well in advance in the case of newly developed areas. However, in the existing city, resilience to heavy rainfall events needs to be developed in a more piecemeal approach due to the many limitations posed by space, budget and time. Construction of the Linnaeus canal is one example of measures that together will help Växjö adapt to the impacts of the changing climate.

Policy context of the adaptation measure

Case mainly developed and implemented because of other policy objectives, but with significant consideration of climate change adaptation aspects.

Objectives of the adaptation measure

The key aim of constructing the Linnaeus canal was to prevent the frequent flooding of the Linnegatan street currently running parallel to the canal. The knowledge gained can be used to manage storm water and reduce the risks of floods in the future and the implementation of this partial solution will buy time for planning and implementation of new interventions. In the climate change adaptation strategy of Växjö (2013), the vulnerabilities of the storm water management system have been recognized and possible solutions such as the development of an investment plan have been drafted.

Adaptation Options Implemented In This Case

Solutions

In the past, there was a small-above-ground stream at the location where the street Linnégatan runs today. The stream served as drainage and led storm water to the inner city Växjö Lake. The stream was built over and enclosed as a result of the street construction in the following years. The new underground canal did not have sufficient drainage capacity after heavy rainfalls, and caused flooding of the neighbouring areas. Moreover, the water that was drained into the Växjö lake took residues, mineral oil and other waste to the lake. By the end of the 1990’s, the City of Växjö started to reopen the canal in Linnégatan, i.e. the Linnaeus canal, in order to prevent the streets and surrounding areas from being flooded and to regulate the flow of the storm water into the lake. The Linnaeus canal functions as a 220 m long storm water storage tank where the storm water is retained and discharged slowly to the Växjö Lake via an underground pipeline and sedimentation lagoons.

Almost all storm water from the central parts of Växjö finally ends up in the lake, potentially increasing its levels of nutrients, particles and heavy metals. In order to prevent this, the water from the Linnaeus canal is discharged into the sedimentation lagoons nearby the lake. After passing the lagoons, the water is discharged into the lake. While the Linnaeus Canal and other types of systems for storage, delay and drainage of storm water have been realized in Växjö, it has also been important for Växjö to reduce the environmental impact on the central Växjö Lake. The canal provides benefits both in terms of environmental and water management targets.

Additional Details

Stakeholder participation

Stakeholder involvement had a significant role in conflict resolution in the planning phase of the canal construction. Initially, instead of lagoons, dams were planned to the City Park next to the Växjö Lake. After the plans were published and made available to all interested parties, citizens and environmental NGOs protested against the plans. After roundtable discussions with these stakeholders and the municipality, the solution to build lagoons came up as a more acceptable option that left the city park untouched.

Success and limiting factors

The project was successful due to the synergies of various functions (storm water management and storage and control of pollutants) and other indirect benefits (related to traffic safety – the project reduces the number of traffic lanes – and urban landscape). The project has shown that it is possible to implement climate change adaptation measures that blend well into the city landscape.

Due to the space limitations of the existing built environment, it was not possible to fully respond to the future climatic conditions with the dimensioning of the canal. However, the canal has served as a partial solution to the current and short-term climate variability, by increasing the capacity of the storm water management system. In new development areas, storm water management facilities are planned to fit both current and future climate changed conditions. Also, potential locations for new storm water management facilities have already been identified on a map and can be built in the future as long as they can be fitted to the city budget. Some solutions to storm water management in the existing city structure have already been implemented in other areas of the city of Växjö to further improve the capacity of the drainage systems. For example, storm water retention ponds underneath a football field and a parking place contribute to management of surface runoff in the city (SMHI).

Costs and benefits

The whole investment cost nearly 2,000,000 €, of which about 15% was funded by the Swedish Government via the Swedish Local Investment Program for Sustainable Development. The remaining part was funded by the Technical Department of the City of Växjö. Thanks to the investment, this part of the city is now mostly protected from floods after heavy rainfalls. The canal is dimensioned to manage the worst rainfalls estimated to currently occur only once every ten years.

Since the construction of the canal, there have been a few floods, but less severe and not as often as before. So, this kind of storm water storage and delay system has proven to be efficient. Due to the projected future amount of rainfall there is a need for further improving measures to prevent flooding in Växjö. Experiences gained within this project will help to develop improved solutions and will provide a valuable example for other municipalities around Europe.

One direct co-benefit of the canal has been that it has contributed to increased traffic safety in the street. The Linnaeus Canal is situated in the middle of the street, outside a secondary school. Before, there was a bigger risk for accidents between cars and people crossing the four-lane street. Now, there are only two lanes and people have the possibility to wait on bridges over the canal before moving on to cross the other traffic lane. Moreover, the canal and the connected sedimentation lagoons contribute to the reduction of the flow of storm water to the lake, and also have a positive effect on the water quality by reducing the amount of pollutants ending up in the lake. The canal is not only an important part of Växjö’s storm water management. The open water body is a beautiful element within the city and also refers to the historic Växjö where a stream was originally situated in this area.

Legal aspects

According to the Swedish Environmental Code, storm water in planned areas shall be considered as waste water. Therefore, storm water is handled by the Environmental Code, which declares what amounts of pollutants are acceptable or non-acceptable. The organization Swedish Water (Svenskt Vatten) has provided recommendations on dimensions of disposal of storm water. These guidelines have become more ambitious since 2015/2016 and clearly refer to “storm water systems” instead just to storm water pipeline dimensioning. Therefore, the guidelines support the adoption of an integrated approach rather just a pure engineering, single solution, as it is the case of the Växjö’s experience.

The Växjö municipality has a policy for water, sewage and storm water (V-A policy, 2014), where it is stated that a long term view and changing future conditions must be considered in planning, dimensioning, execution and maintenance of the facilities. Also, the municipality has a storm water management manual (Dagvatten handbook, 2018) that aims to ensure sustainable handling of storm water Växjö.

Implementation time

The project started in 1998 and ended in 2001 when the Linnaeus Canal and the sedimentation lagoons were finalized.

Lifetime

Lifetime of the canal is likely to be around 100 years. It needs regular dredging of sediments to function properly. The current water capacity of the canal works well under the current rainfall conditions but has to be improved or complemented with other adaptation measures to cope with the projected effects of climate change. As the canal has limited capacity in consideration of future climate conditions, it may need to be supplemented in the future with other storm water management interventions in the area to maintain the benefits that were aimed for initially.

Reference Information

Contact

Malin Engström

Technical department, Municipality of Växjö

E-mail: malin.engstrom@vaxjo.se

References

Växjö municipality, Department of Strategic Planning

Published in Climate-ADAPT: Jun 7, 2016

Please contact us for any other enquiry on this Case Study or to share a new Case Study (email climate.adapt@eea.europa.eu)

Case Studies Documents (1)

Language preference detected

Do you want to see the page translated into ?